- Home

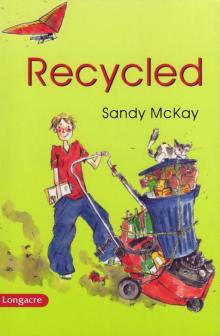

- Sandy McKay

Recycled

Recycled Read online

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter one

Chapter two

Chapter three

Chapter four

Chapter five

Chapter six

Chapter seven

Chapter eight

Chapter nine

Chapter ten

Chapter eleven

Chapter twelve

Chapter thirteen

Chapter fourteen

Chapter fifteen

Chapter sixteen

Chapter seventeen

Chapter eighteen

Colin’s worm farm instructions

Colin’s recipe for making recycled paper

About the Author

Copyright

To our three children – Keri, Hamish and Meg –

the ‘future generation’. Without you I would have

no-one to write for and nothing to write about.

1

“Every year, in the developed world, an average person throws away – 45 kilograms of plastic, two trees worth of paper and cardboard, 160 cans and 107 bottles.”

WHEN OUR TEACHER Mr Read came back after the Christmas holidays we thought he’d flipped his lid. We’d seen it happen before – to Miss Frizell.

It was the end of the year and she started throwing these wobblies for no reason. We’d be sitting there minding our own business and Rodney Stevenson would get bored and flick a paper clip at Lizzie Bennett and she’d yelp like a cat whose tail’s just been stood on and suddenly, out of the blue, Miss Frizell would explode. First, her face would go red as a beetroot, then she’d jam her lips together, squint her eyes up tight and hurl her duster at Rodney’s back (which was all of Rodney she ever saw from the front of the classroom).

One day she stood on the top of her desk and screamed – really loud like she was going for the world screaming record – with her mouth open wide and her tonsils flapping up and down like in a comic book. Ryan Hallimore got so scared he raced over to the principal’s office for help and the principal, whose name is Mr Spittle, had to coax poor old Frizell down from the desk and take her off for a cup of tea. Well, that’s what Willy Hawker said and he should know because he was watching from outside the staffroom window when the tea was poured. By climbing on top of Charlie Webster who’d climbed on top of Shelly Cook he’d managed to get a real good view.

But Mr Read had just had a holiday. I know that for a fact because my best friend Byron Banks had seen him floating on a lilo on Lake Waihola. Byron was having his holidays there and he saw Mr Read three times in a week. Once, floating on the lilo, once crawling out of a blue and white striped tent with a lady in a bikini and once heating up some baked beans in the camp kitchen.

“Gidday, Byron,” Mr Read said. “Nice day for it.”

And now, here he was, two weeks later, looking like he’d just stepped out of a tropical holiday brochure. He was wearing the brightest Hawaiin shirt in the world, a pair of denim shorts that looked like chopped-off jeans and some of those funny sandals like hippies used to wear. All in all he looked pretty relaxed and not at all like he was going to flip his lid.

So why had he come to school with a black plastic rubbish bag and why was he, at this very moment, tipping its contents all over the floor?

“Rubbish!” said Mr Read jamming his lips together and squinting his eyes up tight. “This term we’re going to be learning about rubbish.”

Then he flared his nostrils wildly and started drawing on the blackboard with a stick of red chalk.

REDUCE! RE-USE! RECYCLE! he wrote in big red letters.

Meanwhile the rubbish was tumbling quietly, all over the floor.

“Your average rubbish bag,” said Mr Read, cleverly ignoring the fact that the classroom was now carpeted in soggy cabbage slime, “contains 40 percent kitchen waste, 40 percent packaging and 20 percent paper.”

Byron Banks looked at me like ‘must have been something weird in that Waihola water’ and I looked at him like ‘let’s make a run for it before it’s too late.’

“Rugby after school, Col?” said Byron.

“Yeah!”

The bell was due to ring at any minute and I was starving and the last thing I needed right now was another teacher flipping his lid and the principal having to get a reliever in. It’s disruptive for the kids. We’d just get one teacher trained and then we’d have to start on another. Besides, I liked Mr Read. He was more fun than any of the others by far. Still, it didn’t look good.

Mr Read puddled through the rubbish like an old dog, picking bits out and holding them up. Potato peelings, tea bags, an egg carton, soggy newspaper.

“Did you know that every year in New Zealand three and a half million tonnes of domestic rubbish are thrown out? That’s one tonne for each household.”

“Gee, Mr Read,” muttered Byron, sarcastically, under his breath.

“So where does all this rubbish go? Does anyone know?”

Ryan ‘goodey-goodey’ Hallimore put up his hand. “To the tip, Sir.”

“And then what happens to it?”

“It gets burnt, Sir. Or buried.”

Mr Read looked at our class and nodded forlornly. “Buried.”

“Buried,” he repeated and bowed his head as if we were talking about his very own mother and not a pile of dead food. Then he had a surge of energy and leapt back into life.

“Burying our rubbish is not the answer. Do you know how much rubbish is buried in Auckland city every year? Five hundred thousand tonnes, that’s how much. Five hundred thousand tonnes. That’s the same weight as 166,666 elephants.”

I tried to imagine 166,666 elephants buried together and it wasn’t a pretty sight. Still, there was nothing WE could do about it. Was there?!!

Mr Read obviously thought there was, as he carried on ranting.

“Planet Earth is in a sorry state and we’ve got to save it!” He made it sound urgent, like if we didn’t do anything before next Friday it’d be too late.

“Burying our rubbish is not the answer,” he repeated. “Some rubbish takes more than 50 years to rot away. Even newspapers buried in the ground have been dug up and read ten years later. Rotting rubbish generates methane gas which is smelly, poisonous and could explode. Landfills are bad for the land, dangerous and a waste of rubbish.”

Mr Read looked slowly around the classroom, then whacked his ruler down hard on the desk.

“Recycling. That’s the answer. Recycling.”

The bell rang just in the nick of time.

“For homework tonight I want you all to go home and take some notes about the rubbish your family throws away. Ask mum and dad how much they get rid of each week and think about some of the ways we can reduce the amount of rubbish we make.”

He looked up and grinned.

“We’ll discuss it in class tomorrow.”

We stopped at the park on our way home as usual. I had one dollar left over from my pocket money so I bought a bag of mixed lollies. Byron, who always has heaps of money, got a can of lemonade and a pie.

Charlie, Tom and Phillip were kicking the ball around the park and after I’d finished helping Byron eat his pie we raced over to join them.

Phillip was practising his goal kicking because the coach said he’d give him a go on Saturday if he did okay at training. He’d been wanting to be the ‘kicker’ for ages but Carl Van der Loo always beat him to it because his Dad was assistant coach.

He was trying out a drop kick and when he booted the ball hard it soared over the posts and bounced onto the road.

“Magic, Phil. Magic,” I yelled. “I’ll get it.”

Then something weird happened.

I was about to race across the road for the ball when a bright green Mazda came really fast around

the corner. I nearly didn’t see it. Then it slowed down and some moron with a shaved head opened the door and heaved out a pile of rubbish.

Fish and chip papers, a couple of Coke cans, a cigarette packet and something that looked like a milkshake container were hurled onto our park.

“Hey,” I called out. “What do ya think you’re doing?”

I couldn’t believe someone could do that. Just chuck their rubbish onto a park like that.

The car sped off, then it changed its mind, did a U-ey and came hooning back. It jumped clean off the road, screeched to a halt on the footpath and nearly knocked me flat. The guy with the shaved head leaned out of the car. He had a cigarette in his hand and he flicked the ash at me like I was an ashtray or something.

“What are ya gonna do about it, poofter?” he sneered. I said nothing, just looked at him and felt my face go red and hot with rage.

What could I do?!

Then the car jerked back onto the road and took off. The shaved head guy had his arm hanging out the window and shoved his middle finger up in the air. Willy Hawker did that sign once to a teacher at school and nearly got expelled. ‘Dick-head,’ I thought. What a creep.

What a drongo. What a moronic, low-life, waste-of-space, dead-head.

Who did he think he was? Who did he think was going to clean up his mess? What gave him the right?

I couldn’t get it out of my mind and now I knew Mr Read had been telling the truth.

Planet Earth was going to the dogs and we had to do something before it was too late…

2

“The world’s largest landfill, near New York City, holds 68 million cubic metres of rubbish – 25 times the volume of one of the great Egyptian pyramids at Giza.”

IT WAS HARD TO BELIEVE that yesterday I was a happy-go-lucky kid whose only worry was whether Lizzie Bennett would speak to me or not. Today I was an eco-warrior with the future of Planet Earth weighing heavily on my undeveloped shoulders. (My sister calls them puny: I prefer undeveloped because it suggests hope for future development).

When I got home for dinner I had a poke around the rubbish bag in the kitchen and made some notes on the contents. It did not make exciting reading.

Soggy potato peelings, two plastic milk containers, some old rice that looked like it had been in the fridge since last summer, a crushed up Weet-bix packet, last night’s left-over beef stew, a newspaper, Dad’s favourite T-shirt, junk mail with supermarket bargains, a school notice, an empty sour cream pottle, one small plastic Marmite jar, three biscuit packets, a Lynx deodorant bottle, Allie’s lunch (still in its plastic), the cardboard from a pair of sports’ socks Dad had bought and something green that looked like it used to be a lettuce.

I could think of better things to study but I had to admit it did have its interesting side. Like why was my sister Allie’s lunch in the bin and did Dad know about the disposal of his favourite T-shirt?

I bet you could uncover a lot of every family’s secrets from the contents of their rubbish bins.

Mum was in the door just two minutes before she started on at me, which was two minutes better than yesterday.

“Co-o-o-lin. What do you think you’re doing?” she asked in that weary tone of voice that meant she didn’t really want to know but thought she better ask anyway.

I ignored it. I had an important job to do.

“How much rubbish do we have in a week, Mum?”

“Oh, I don’t know. About three of those black bags full, I guess. Why?”

“About three of these, all full up?”

“Yeah, I guess so. More or less. Sometimes more and sometimes less. Why, what are you up to?” (Why is it that mothers always assume you’re ‘up to’ something?)

“It’s for school. A project on rubbish.”

She shrugged her shoulders.

I brought the bathroom scales downstairs and held the rubbish bag on top for a weigh-in. Seven and a half kilos. If we had three of these each week, that came to a grand total of… of… I used my calculator – 22.5 kilos.

Mr Read was right.

I tried to imagine this much rubbish in the ground every week for every year for everyone in the country. It was a disgusting thought.

“If we wanted to have less rubbish, Mum, what would we have to do?”

“Stop eating,” she said just as I was about to take a bite of a Marmite and cheese sandwich. Allie thought this was a great joke. “Him… stop eating…” and she pretended to choke on her carrot. “And pigs might fly…”

Allie, my sister, had a strange relationship with food. She went on about it all the time but never actually got around to eating it. Well, not proper food. Just carrots and apples and skinny little biscuits that taste more like cardboard than food. She hadn’t had fish and chips for weeks and got through so many cans of Diet Coke in a day that it was a wonder she hadn’t turned into one. She had been on a diet forever and if you asked me she still looked the same as when she started.

I couldn’t work out why anyone would want to starve themselves just so they could wear smaller clothes. Her friend Monica was exactly the same. I heard them on the phone one day. They talked for half an hour about how many calories were in the hokey pokey ice cream Monica had scoffed in the week-end.

Man, it was pathetic.

Anyway, enough about that. I’d been thinking about all our family’s rubbish and I’d come up with a few choice ideas.

With a few minor alterations to our routine, I was confident we could cut our rubbish pile in half. No sweat. I simply analysed the contents of the rubbish bin and came up with a plan to eliminate all unnecessary items.

There were three key points to my plan:

1. We would go back to glass milk bottles from the ‘milkman’;

2. We would ban all canned food and;

3. We would put a ‘no junk mail’ sign on the letter box and cancel our daily newspaper.

The family wasn’t so keen.

“It’s okay if you’ve got all day to spend in the kitchen,” said Mum – making excuses already. “I’m a working mother, Col. I’ve got houses to sell.” (I’ll tell you more about this in the next chapter.)

Dad reckoned the no-newspaper idea was barmy. “How will I know if there are any good jobs?” he said. (Dad is out of work at the moment. I’ll tell you more about this later as well.)

And Allie, my big sister, was her usual unhelpful self.

“And who will remember to put the milk bottles out?” she said sarcastically. “You can’t even remember to take your mouth guard to rugby practice!”

This was going to be a bigger job than I thought.

3

“Recycling aluminium cans requires 95 percent less energy than making new ones.”

BEFORE WE GO ANY FURTHER I better introduce you to my family.

Byron Banks reckons we’re a weird bunch but then his family is really boring. His Dad has been an accountant in the same office for 23 years and his Mum spends all day shopping in town or planning her next dinner party.

Well, that’s what my Mum reckons. Byron says she’s probably jealous. I know I am.

They’ve got a flash house and heaps of money so there’s nothing for them to argue about and Byron, being an ‘only child’, has no-one to fight with either. Which is sweet, I guess. Our family fights quite a lot.

I’ll start with Dad. He’s ‘in between jobs’ just now. Well, that’s what he calls it. Mum calls it ‘unemployed’ but Dad hates that word. ‘Unemployed’ sounds like it means forever, he says. They’re always talking about the ‘unemployed’ on the TV news – people moan about how they get too much money and waste it on cigarettes and don’t look after their children properly. Well, that’s not my Dad. He doesn’t smoke anymore and he looks after me and Allie just fine.

Dad’s name is Bob Kennedy and he’s 39 years old. He worked most of his life as a fitter and turner (whatever that is) at Downdale workshops. Then he got laid off about six months ago and he’s been looking for

work ever since. Unfortunately there’s been a ‘down turn’ in the economy – well, that’s what they say on the news – and jobs are hard to get. Especially in Southsville, which is almost at the bottom of the world. Apart from Invercargill that is. Ben Roberts, who used to sit beside me at school, went to live in Auckland last year and he says there’re heaps of jobs up there. But Mum and Dad say houses cost too much in Auckland and all their friends are down here as well as Nana and Grandad and Aunty Rose and besides, they like it here, so why should they have to move? Ben Roberts doesn’t even like Auckland. He’s been there for nearly a year and it hasn’t snowed once.

But back to Dad.

Dad’s real good with his hands and he’s always mucking about in the garage fixing things. Machines and stuff. He’s got 15 lawnmowers in his garage – none of them go yet but he reckons he’s going to get them up and running and make a fortune!

Mum thinks he’s mad. She reckons he spends too much time in the garage and he should be doing some ‘retraining’ instead. She says her friend Pam’s husband Barry went to Polytech for ‘retraining’. He did a course in business management and now he’s got a real good job with the City Council. Dad says that’s not for him and besides, with Mum working, at least we’re getting some food on the table.

Mum has a job selling houses. Real Estate, it’s called. She gets her picture in the paper on Saturdays and her very own cellphone which sometimes rings at embarrassing moments. Like once we were at the movies and it got to the part where they were trying to stop a bomb going off. Very carefully, da da dum… da da dum… slow music, everyone on the edge of their seats and suddenly… bling, bling… that’s Mum’s cellphone ringing beside me. The man in the row behind us leaned over and said ‘turn that bloody thing off’ and Mum told him to mind his own bloody business and I spent the rest of the movie slunk down so low in my seat that I couldn’t even see the screen.

Another time we were at the doctor’s and the phone starts ringing in her bag. She picks it up and starts yapping on about some bungalow with ‘great potential’. The doctor was in the middle of burning a wart off my finger and then he gets interested in the ‘bungalow with great potential’ because he’s looking for a house for his Mum who lives on a hill and wants to get down on the flat and then Mum gives him her business card and makes a date to meet him and show him around. And the next minute we’re paying the receptionist and I’ve only had one wart removed and it was meant to be five.

Losing It

Losing It When Our Jack Went to War

When Our Jack Went to War Recycled

Recycled